When Frances, Viscountess Purbeck, meets Sir Kenelm Digby toward the end of the 1630’s in Nights of the Road, she is a woman on the run from her country, her church and her king. Her staunchest supporter in Paris, where she has sought refuge, is this man who is larger than life in every sense.

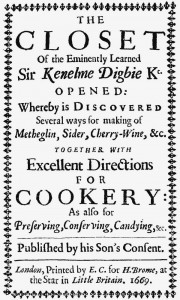

Courtier, diplomat, alchemist, scientist, philosopher, privateer, author and poet, preparer of ‘Sympathetic Powder’ for the wounded and collector of High Society’s cooking recipes, the much-travelled widower must have been an entertaining companion as well as a reassuring presence for Frances.

A reputed lady’s man, Digby may well have bestirred himself on behalf of Lady Purbeck because of her beauty. Yet it was also in character for him to extend a helping hand to others. Sir Kenelm devoted energy to calming and easing difficult relations in many situations, although captains of Mediterranean vessels that fell victim to his early privateering might have considered him also a significant creator of discord.

Whatever his motives, Digby took up Frances’s cause enthusiastically, with Cardinal Richelieu and the King and Queen of France, and also with English diplomats and politicians like Scudamore and Conway. He even appealed directly to the man who had spearheaded Lady Purbeck’s persecution, his own former tutor, Archbishop Laud.

It’s hard to gauge the credit due to Digby for restoring Frances to favor, any more than to assess his effect upon her religious journey, since we have his written record rather than hers. We do know that she ultimately received her royal pardon; just as we know that she converted to Catholicism during her time in France …

In earlier years Digby had been employed by his kinsman, the Earl of Bristol in an attempt to mend fences with Majesty concerning his (Bristol’s) differences with the Duke of Buckingham after Spanish Infanta fiasco. Much later, and long after Frances had quit Paris, Sir Kenelm Digby also beat a diplomatic trail to Rome, this time as Queen Henrietta Maria’s envoy to the Pope.

In earlier years Digby had been employed by his kinsman, the Earl of Bristol in an attempt to mend fences with Majesty concerning his (Bristol’s) differences with the Duke of Buckingham after Spanish Infanta fiasco. Much later, and long after Frances had quit Paris, Sir Kenelm Digby also beat a diplomatic trail to Rome, this time as Queen Henrietta Maria’s envoy to the Pope.

Digby had limited success on both counts. He met Charles I concerning Bristol, and wrote an effusive letter to the Earl, reporting that the King was conditionally open to receiving him back in the royal fold. Yet Bristol still took up obligatory residence in the Tower a year later. That may have been due as much to Buckingham’s hatred and Bristol’s refusal to recognize having committed any wrong against the King’s friend, as to any faults in Digby’s peacemaking skills.

In Rome, however, Innocent X reportedly took serious umbrage at what John Aubrey described as Sir Kenelm’s ‘hectoring’ and Wood referred to as ‘Huffing his Holiness’. But her man still got the Queen some dibs out of the encounter, to the immediate tune of 20,000 Crowns (more than $1 million today), and with the promise of more if a treaty could be obtained with the English court.

Digby’s biographer Thomas Longueville suggested the Pope might have been at least as much upset by the funds being used on Protestant King Charles’s war effort, instead of distressed Catholics, as by the Queen’s envoy’s high-handedness. In any event, Henrietta Maria would have nothing to do the proposed treaty and, next time she sent an envoy to Rome, she ensured he was briefed to avoid the ‘rocks’ that Digby had touched.

The more I’ve researched Kenelm Digby, both before and since writing Nights of the Road, the more intriguing I find this man, and also the more uncertain I’ve felt about his essential nature. Was he a cultured and confident courtier of moral integrity, brilliant and versatile in his intellectual interests and practical skills? Was he rather a clever and self-promoting charlatan who had a great sense of time and place, combined with a capacity to coattail on other men’s work and wisdom? Oh, and just how did Sir Kenelm treat his wife, who died young?

For every yea-sayer, I’ve discovered a naysayer; for every attested tale praising Digby’s wooings and doings (often himself), I’ve unearthed a skeptic if not an outright critic. But that Digby was both unusual and a memorable personality I am left in no doubt, and that he evades simple categorization is clear from the diverse viewpoints expressed by his contemporaries and since.

For every yea-sayer, I’ve discovered a naysayer; for every attested tale praising Digby’s wooings and doings (often himself), I’ve unearthed a skeptic if not an outright critic. But that Digby was both unusual and a memorable personality I am left in no doubt, and that he evades simple categorization is clear from the diverse viewpoints expressed by his contemporaries and since.

Kenelm Digby is one of those characters I’d really like to travel back through time to meet for myself, to draw my own impresssions. If I could meet him, I’d first ask how the son of a knight who was hanged, drawn and quartered for trying to blow up King and Parliament could have been accepted so smoothly within royal circles.

Since Kenelm was still only two when Sir Everard Digby was executed for his part in the Gunpowder Treason, it is just that sins of the father should not be visited upon the son. Yet there must have been continuing questions about the family’s allegiance.

Since Kenelm was still only two when Sir Everard Digby was executed for his part in the Gunpowder Treason, it is just that sins of the father should not be visited upon the son. Yet there must have been continuing questions about the family’s allegiance.

The little boy may have been fortunate in growing to manhood during the reign of a natural peace-lover like James, rather than that of his more vindictively disposed son or even that of his grandson, during whose monarchy nearly every living regicide and members of their immediate family were called to count. Dead ones too…

When we trace Kenelm Digby’s career, we find him already embraced by society at his majority, and riding high enough in royal favor to be installed as Gentleman of the Bedchamber and later as a member of Charles I’s Privy Council. His loyalty to his king is beyond doubt when he kills a Frenchman in a duel for daring to call Charles ‘the arrantest coward in the world’.

At the outbreak of Civil War, Digby is not in the thick of the fight although his son is, and gets killed at St Neots. Why not? He has been a privateer who scored several naval victories across the Mediterranean, from Gibraltar to the coast of Turkey. He’s also younger than many a serving Royalist officer and Van Dyck has already shown that he owns a dashing suit of armor.

It turns out he has already been arrested. He spends a couple of productive writing years as Parliament’s ‘guest’ in Winchester House, before the Queen Mother of France, Marie de Medici (who had reportedly fallen for him years earlier) intercedes to secure his release and receive him at the French Court. There he remains until after the war.

It turns out he has already been arrested. He spends a couple of productive writing years as Parliament’s ‘guest’ in Winchester House, before the Queen Mother of France, Marie de Medici (who had reportedly fallen for him years earlier) intercedes to secure his release and receive him at the French Court. There he remains until after the war.

Yet, soon after Oliver Cromwell dismisses the Long Parliament and assumes supreme power, we find Sir Kenelm back in England and extraordinarily “in very good favor with the Lord Protector”, all the while remaining Chancellor to Queen Henrietta Maria in exile. He even writes to John Thurloe, Cromwell’s secretary and spymaster: “Whatsoever may be disliked by my Lord Protector and the council of state, must be detested by me.”

Hmm. I’d want to ask some questions about this part of his life, for sure.

After this, it comes as no surprise to learn that Sir Kenelm finds a way to secure his place in Charles II’s Restoration England. Even if he is reported as irritating his new King and being forbidden the court in 1664, Digby nonetheless remains in good relationship with Charles’s mother to the end, and mixes freely with leading members of society at Gresham College and his Covent Garden home.

There in his twilight years we may observe him actively engaged in conducting experiments in the laboratory he has set up in his home, while also co-founding the Royal Society. It is a long recurring struggle with ‘the stone’ rather than royal disfavor that brings about Sir Kenelm Digby’s demise in 1665.

I do find myself marveling at the capacity of Kenelm Digby during his 62 years to ‘have run with the hare and hunted with the hounds’. Yet a comment from the editor of Longueville’s 19th century biography also stays with me: “Sir Kenelm Digby did go from one side to the other – in religion, love, loyalty and politics… It was the habit of the age – an age in which nobody ought to have lived. He did top the others in that, despite the age’s dishonorable tendencies, he wore and kept the robes and trappings of a gentleman of honor.”

My favorite one-liner about Digby comes from Hermione Eyre, whose novel Viper Wine, published in 2014, is nominated for the 2015 Folio Prize and shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize. Her book centers on the story of Kenelm’s marriage with a society beauty and particularly on the sad circumstances surrounding Venetia’s death at age thirty three.

Eyre says pithily: “Sir Kenelm was one of the great over-achievers of the English renaissance”. Her journalistic skills are also on display when she describes Digby thus: “He discoursed with Descartes, befriended Cromwell and was a Gentleman of Charles I’s bedchamber. He was the first to recommend bacon with eggs for breakfast; he was the last to believe that wounds could be cured by treating the weapon that caused them with the Powder of Sympathy. He has a cameo in a novel, The Island of the Day Before, by Umberto Eco; his name is used by Aldous Huxley in The Devils of Loudun to invoke the backwardness of the 17th century. He is one of those people whom one starts to believe might have been capable of anything; a time-torn inhabitant of many ages at once.” http://tinyurl.com/mhpdfc6

Hermione Eyre is an Oxford graduate who once spent a season as a croupier. Both aspects of her education may have fitted her for the job of Contributing Editor at the London Evening Standard’s ES Magazine. As interviewer and book reviewer, she contributes to publications ranging from The Times, The Financial Times and The Spectator to Harpers Bazaar, Elle UK, and Prospect.

A Guardian book review of Viper Wine reads: “Using an alchemy all of her own, Eyre’s postmodern take on the 17th century renders it dazzlingly fresh and contemporary.” The Telegraph says: “The stylistic brio and technical invention on show here is truly impressive.”

A Guardian book review of Viper Wine reads: “Using an alchemy all of her own, Eyre’s postmodern take on the 17th century renders it dazzlingly fresh and contemporary.” The Telegraph says: “The stylistic brio and technical invention on show here is truly impressive.”

I cannot yet speak usefully about Eyre’s book. Despite several attempts, I haven’t settled into Viper Wine. I keep getting stuck at its third chapter. Judging by Goodreads reviews, I’m not the only one who feels confused. I shall persevere, however, and not because Viper Wine has been nominated for prestigious prizes. No, it’s because of that one phrase Eyre used to describe Digby: ‘a time-torn inhabitant of many ages at once’.

However tricky I find the novel’s construction and style, I do sense Eyre may have captured something essential in Sir Kenelm Digby, and I want to see the whole picture she paints of his elusive character. For, after all my own researches, I still have so many questions, but my gut has been telling me that his spirit belongs beyond the confines of a single age.

Digby would surely have thrived in our present times. A man so convinced and capable of convincing others that a salve of ferrous sulphate could cure a wound when applied to the weapon that created it must have been at center front, observing and participating too, as third millennium scientists search to unfold mysteries of quantum physics, field dynamics and distance healing. I imagine Kenelm chatting animatedly with Rupert Sheldrake: enthusiastically embracing all aspects of morphic resonance, and butterflies flapping their wings around the world, as well as that vital hundredth, sweet-potato-eating monkey.

Yes, I can see him now, sticking his fingers in exploratory scientific pies in our 21st century ovens of exploration, and then rushing off to add every new recipe to his growing 21st Century Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby Knight. He would surely then follow that by leaping to blog and share his latest adventures on Facebook and Twitter.