I enjoyed a brief and pleasant exchange with the Casebooks Project after last week’s blog, during which I learned that my curiosity concerning Richard Napier’s case notes on John Villiers will probably only be satisfied during the late spring of 2016. So I continue to plough my lone furrow and search among online breadcrumbs for clues about Viscount Purbeck’s life.

A few interesting snippets I’ve turned up this week include a miniature of Purbeck’s second wife by the well known English artist Samuel Cooper:

Samuel Cooper by unknown engraver

Samuel Cooper by unknown engraver

Elizabeth Slingsby was the daughter of a Yorkshire worthy, Sir William, and niece to Sir Henry, executed for zealous and sadly premature attempts to encourage the Hull garrison into declaring itself for the King, just two years before a Stuart was restored to the throne and Charles II was received in London to tumultuous acclaim.

Elizabeth was elder sister to another Henry, who was made Life Master of the Royal Mint during the Restoration. Not the safest hands for such a sinecure, as it turned out. Brother Henry was expelled from the Royal Society in 1675 for non-payment of dues and suspended from the Mint in 1680, on grounds of incompetence and likely financial irregularities. He died hopelessly in debt in 1690.

Elizabeth did not fare well in her first marriage. Colonel Chichester Fortescue, an MP and soldier of Dromiskin Ireland died in the Siege of Drogheda, during the Irish rebellion of 1641-2, only three years after they were wed.

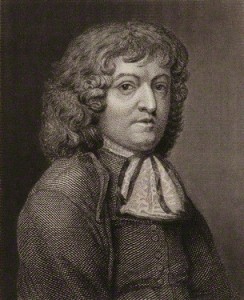

The Siege of Drogheda 1641

(for an account of this period in Irish history see http://arranqhenderson.com/2012/12/18/st-patricks-4-jones-rebels-confederates-cromwell-17th-century-horror-in-ireland/2935221ca2e3e6cc0000d15d4d515e77-1913618185-1300419192-4d82d278-620×348-4/ )

As a young widowed mother of an infant daughter, Elizabeth was immediately obliged to seek recourse in law for financial support that her father-in-law had promised in the marriage settlement to his son’s new wife and family, but neglected to deliver by the time of Chichester’s death. The law backed Elizabeth and ordered Fortescue not to leave the country until he had straightened matters out. Sir ‘Faithful’ had a hard time living up to his name in more ways than one. Like many, he changed sides several times and fought for both King and Parliament during the Civil War, before being arrested in Wales and imprisoned in Caernarvon Castle for desertion.

Fortescue’s sympathies lay long-term with the Royalists, however. He escaped with Charles to Scotland and lived on the continent with other court exiles, before having his Irish lands restored to him by Charles II in 1665. If his faithfulness was in doubt, his longevity was not. He buried three sons and lived to the ripe age of 85, by which time Elizabeth had been remarried for nearly twenty years.

How did Elizabeth feel about marrying again, in 1646 at Brooksby in Leicestershire at the age of twenty-seven, to a Royalist but non-combatant husband, who could no longer rely on the protection of a beleaguered Charles I? Was she prepared for possible extremes of mood in her husband? I’ve found little evidence yet about the nature of his health or of their life together.

Elizabeth Slingsby, Viscountess Purbeck

For now there simply exists this miniature, oval in shape and three inches long by two inches wide. In it Elizabeth looks to her left, wearing an amber dress with a blue scarf. Her necklace is nondescript, but a single large pearl is tied with black ribbon to the center front of her dress. I see a slender woman with large, limpid eyes and a mournful gaze; the kind of woman I sense that some might feel drawn to protect, and others – like myself – inclined to mistrust.

Why do I feel such antipathy, from one black and white image – not even the original – of a tiny painting nearly four centuries old? I catch myself feeling subjectively partisan from the first moment I gaze upon Elizabeth Slingsby. “Huh” I hear myself say. “Not a patch on his first wife for looks or personality.” There i go, reacting just like a long-time friend of the bride, who looks askance at her ex-husband’s new choice of companion before even giving the woman a chance to be seen and appreciated for herself…

And at that I bring myself up short. Who am I to infer anything from a single portrait? How may I judge of the character of this girl/woman born into one of the most troubled times in history, who reportedly had to struggle just to receive her just dues from her first marriage? Why should I feel any less warmth for Elizabeth Slingsby than I had and have for Frances Coke? Why indeed?

I can only put it down to some strange fact of personal chemistry and/or my own rampant prejudices. For all I know, Elizabeth Fortescue nee Slingsby was a lovely soul and already deeply in love with Purbeck when she became his Viscountess. For all I know, she proceeded to put all John Villiers’ cares and concerns before her own and to act as an endearing and compassionate wife. For all I know, Elizabeth enjoyed a rich and interesting personal life while also giving John Villiers much needed companionship in his final twelve years. She may have been an independent woman and doting mother, mother-in-law and grandmother…

In truth, notwithstanding all my searches to date, I still know nothing of whether John Villiers himself was well or disturbed, happy or sad, during his final years. I don’t receive any messages through the ether about his emotional condition after Frances passed. The last ‘facts’ I have established for Purbeck are: his re-marriage in 1646; his will of August 1655, in which he leaves ‘all my estate in all and personall whatsover unto my most deare and loving wife, the Ladie Elizabeth Viscountess Purbeck, whom I nominate and appoint sole executrix of this my last Will and Testament, freely to be disposed of at her Pleasure’, and finally his death at Charlton in Kent on 18 February 1658.

‘Most deare and loving wife’? Hmm…

Elizabeth is reported as having retired permanently to Yorkshire after being widowed a second time. At forty, she had already reached the average life expectancy for her times, yet she lived on another thirty-eight years. She appears to have spent the rest of her life with her daughter and son-in-law, Richard Graham, who had inherited a comfortable mansion known as Norton Conyers House in North Yorkshire from his father. That handsome mediaeval manor with its Stuart and Georgian additions is now believed to have been the inspiration for Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. See why at: http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/dec/04/books.booksnews

Norton Conyers House ©www.ansonphotography

Norton Conyers House ©www.ansonphotography

Still owned by the Graham family after nearly four centuries, Norton Conyers House is a member of the Historic Houses Association and open free to the public, although closed when used for weddings and also undergoing restoration. http://nortonconyers.org.uk

About the second part of Elizabeth’s life, I have gleaned only a few additional crumbs. She was certainly comfortably situated, for she had jewelry, plate and money aplenty to dispose of at her death. She had already inherited her mother’s pearl necklace and plate at the time of Lady Slingsby’s death in 1655. Was this the same ‘neclace containing fourscore and 14 pearles’ that she in turn bequeathed in 1696 to her granddaughter the Lady Elizabeth Fenwick, and the ‘2 silver plates marked WS’ left to her sister-in-law Ann, with the request that she in turn bequeath them to her daughter Elizabeth Slingsby ‘that they may not go out of the family’? Lets hope Ann was not obliged to sell the plate immediately, given that dead husband Henry had left her in such a parlous financial condition.

That phrase: ‘that they may not go out of the family’ does suggest to me that Elizabeth probably identified herself first and last as a Slingsby rather than a Fortescue or a Villiers although, unlike Robert Villiers-Danvers (known as Robin in Nights of the Road), a man she might have chosen to claim, but did not, as ‘stepson’, she retained her Purbeck connection and the dowager title, to which she was entitled after John Villiers died. If keeping property within the family mattered to her as much as it appears to have, she must be pleased that, four hundred years on, the family her daughter married into still owns the house where she spent half of her life. And a house with an interesting story of its own.

Was Elizabeth, like her husband Purbeck, a Catholic, in a century when to be so openly was dangerous? We cannot be definitive. Her niece was named during the reign of Charles II in a True Bill against 117 recusants for ‘not going to church, chapel or any other usual place of common prayer during one month’ in Middlesex County Records. Elizabeth was entertained to supper by the controversial Dr Thomas Cartwright, Bishop of Chester, after he had preached at Ripon in 1686.

Dr. Thomas Cartwright, Bishop of Chester, University of Oxford, Queen’s College, Attributed to Gerard Soest 1680

Cartwright was ordained a Protestant but his religious convictions were questioned frequently during his flamboyant and notorious career, especially after he fled to France to join his beloved royal master, James II, after the Glorious Revolution. Yet he read the Liturgy of the Church of England to Protestants during exile in his lodgings in Saint Germain. Some have adduced, from his sermons and reportedly failed attempts at his deathbed to read him Catholic rites, that Cartwright actually felt an aversion to Papery.

The preface to his published diary printed in 1843 for the Camden Society contains the equivocal comment: “We find throughout, this Protestant Bishop in constant communication with the Roman Catholics of the time, both those whom he found in his own diocese, and those who were more especially the agents for the Court of Rome, in the design of re-uniting England to the Church of which Rome was the head, and communicating with them apparently on matters of the greatest importance to the well-being of the church.”

That Elizabeth was of a strong religious inclination, whether Catholic or Protestant, seems likely. She dedicated a communion cup to her native parish of Kippax in Yorkshire in 1679 and the terms of her will reveal that she wanted due care and decorum observed at her funeral. She was to be conducted to church in a hearse. To ensure that all her kin and servants would be appropriately dressed for the occasion, she left sums significant in size for the day, to be used for purchase of mourning apparel.

Elizabeth was buried according to her wishes in All Saints Parish Church at Wath-upon-Dearne in Yorkshire on 23 January 1696.

Elizabeth Slingsby, Viscountess Purbeck, outlived her only sibling and two husbands and survived three-quarters of one of the more tumultuous centuries in British history. She may have a good many interesting tales to tell.

Perhaps I shall warm to her company with time…