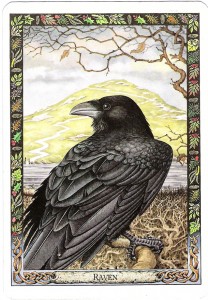

This week’s blog owes its being to a recent fight above our garden. I live in the land of the red-tailed hawk, a bird that nests in the crowns of high trees on the hill behind our house. The hawk is not popular with the two ravens that regard our back yard as their own.

Have you ever seen ravens ‘mob’ a bird of prey? It is common here in Southern California. Check out YouTube for videos of such encounters or see on Facebook some great photos of a mythic battle enacted by the ocean.

Watching the latest fight, I observed that, whatever the smaller birds might lack in size, they make up for in strategy, stamina and speed. As the ravens called up neighboring reserves to wage an all-out war on the stubbornly immobile hawk, I began thinking of Bran the Blessed, sometime mythic King of Britain, and his legend associated with the Tower of London. Do you know it?

I’m named after Bran’s sister (Midi being a later acquisition), and ingested the story very young. Like all good myths, it is both ancient and modern, and so contains a fresh message for our times.

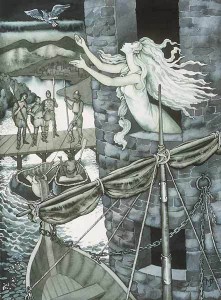

In the Mabinogion, the ancient oral collection of Welsh stories for which written records date back to the twelfth century, the giant Bendigeidfran or Bran (meaning ‘raven’) heads for Ireland to rescue his sister Branwen (my namesake) as soon as he receives a message of distress from her carried by a starling. Her husband’s family are mistreating her in revenge for an insult suffered earlier in Wales, when Bran’s half brother Effnisien mutilated the Irish king’s horses.

The Irish declare they’re ready to make peace and be nice to Branwen. The infamous Effnisien suspects their hosts of laying a trap for the Welsh, or perhaps he just wants another excuse to brawl. Whatever the reason, he kills Branwen’s son, Gwern. In the pitched battle that ensues, only seven men survive to take their dead leader Bran’s head, still speaking – this is a Welsh tale, after all – back to Harlech Castle with Branwen. Bereft of her son and brother, she dies of a broken heart. http://www.celtictwilight.com/camelot/mabinogion/branwen.html

The seven men remain in Harlech for seven years, entertained by and entertaining the talkative head of Bran. Then they travel through a portal into another dimension, moving to one of those Blessed Isles off the coast of Wales that exist outside time and form the core of a Celt’s natural dreamscape.

Fourscore (eighty) years pass in earth time while they eat and drink and make merry. By now, Bran’s head has done with talking. His men gaze back through the portal and see an impoverished and oppressed land of Cornwall. They recall the sacred promise made to their leader, when a dying Bran commanded them to take his head to London and bury it under the White Mount, facing toward France.

Bran’s faithful followers are led by Owain. That is my maiden name, so I feel even more personal attachment to the story. The men travel east and bury the head under what will be the site of the Norman-built Tower of London. And now according to a Welsh Triad they have fulfilled one of the Three Fortunate Concealments of the Island of Britain.

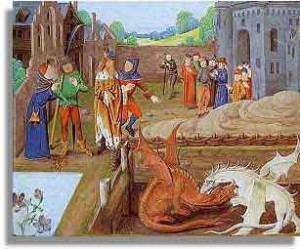

The other two are the Bones of Gwerhefyr Fendigaid, buried in various ‘great ports’ around the coast, and the Dragons which Lludd ap Beli or Lugh of the Silver Hand, Celtic god of health and healing, captured at Oxford – center of the ancient kingdom – and buried in Dinas Emrys in Snowdonia, deemed to be the strongest part of the island.

As long as all three concealments remain in place, no further oppression will come to island Britain.

Unfortunately, prophecies don’t prevent people digging up trouble. In legend, Vortigern is the man said to have disinterred his father’s bones from the island’s eastern seaports, all for love of the Saxon Rowena. Hah! Might have guessed a woman would be involved. So there goes England, open to an Anglo-Saxon invasion from the east.

Vortigern is the culprit again with the second of The Three Unfortunate Disclosures, even though Emrys Wledig, who may be Roman soldier Ambrosius and/or the Druid Merlin, spills the beans on the whereabouts of the two sleeping dragons. Difficult to blame Emrys, since Vortigern was set to sacrifice him to the gods, because the fortress tower erected at Dinas Emrys keeps falling down. There goes strike number two. Only a matter of time now before ancient Cymru is a goner…

Bad behavior might have been anticipated from Vortigern, called ‘usurper’ and ‘tyrant’ by Gildas and one of the Three Dishonour’d Men in a Welsh Triad. But a dreadful disappointment is still in store. None other than our Golden Boy of Camelot, Arthur, commits the third Unfortunate Disclosure. He digs up Bran’s head for no better reason than feeling Britain should be defended by his own military might, rather than that of a ‘deadhead’. See where hubris can lead a king and his kingdom?

Thus goes the tragic tale of how the gates of island Britain were flung open again to invasion and oppression.

You may be asking how we get from some tall Welsh tale of yesteryear to a Tower of London that today employs one uniformed Yeoman Warder Ravenmaster specifically to care for six plus one ravens with clipped wings from dawn to dusk, and thereby ‘ensure’ that the Crown and the Tower will be safe from further invasion and oppression?

You’ll find some charming photos at http://www.seamepost.com/europe/ravenmaster-deaths-at-the-tower-of-london-end-of/ , where you may also learn about a day in the life of a Yeoman Warder Ravenmaster and his charges, as well as the story that we owe it all to Charles II.

Yes, the Merry Monarch is reputed to provide a seventeenth-century link with the legend of Bran and the White Mount. The story you may get, if you join the more than two million (I did say ‘million’) tourists who visit the Tower of London each year, is that ravens obscured the view of the royal astronomer John Flamsteed and irritated him with their chatter, so he asked Charles II to get them gone.

Someone then is said to have reminded the King about the legend, which morphed symbolically into the monarchy and the country being doomed if ravens deserted the Tower. Ever of an inventive and practical nature, Charles reportedly came up with a plan. He ordered that just six ravens be kept at the Tower, with a seventh in reserve for luck. All must have one wing clipped, to prevent their departure.

I feel dissonance with this story. Seven ravens can still create a mighty chatter – I testify to that, after living alongside just the two that own our garden. Would Flamsteed really have been satisfied? And wouldn’t clipped ravens be ‘sitting ducks’ for other predators?

Scholarly study by an independent researcher from White Plains NY, with a doctorate and the splendid name of Boria Sax, led him to debunk the story of Charles. He shared his doubts with the official historian of the Tower of London, Dr. Parnell, who concurred and told the Guardian that it might have all been a nineteenth century flight of fantasy designed to beef (eater?) up the atmosphere surrounding tales of executions told to tourists. http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/nov/15/britishidentity.artsandhumanities

Dr. Sax’s 2012 book is called City of Ravens: The Extraordinary History of London, the Tower and its Famous Ravens. It’s available at Amazon, where its blurb reads: “The tales tell that Charles the Second feared ‘Britain will fall’ if the ravens ever left the Tower of London. Yet the truth is that they arrived in Victorian times as props in gory tales for tourists.” Dr. Sax also wrote an article for Society and Animals that you can download from Internet: https://www.animalsandsociety.org/assets/library/737_s4.pdf . It details his search for evidence of when the birds were first depicted at the Tower.

Dr. Sax also gives time and space to early twentieth century writings of a Japanese, Natsume Soseki, who suggested the ravens embody the shape-shifter spirits of Lady Jane Grey, Sir Walter Raleigh, and others imprisoned and executed at the Tower.

I can understand, in a macabre, bottom-line-oriented way, why one might wish to embroider the story of executions at the Tower of London, especially if two million entrance-paying tourists are eager for gore. Are they? Apparently the ravens are the number two attraction after the Crown Jewels. But if it is gore they want, they might prefer to visit the state of Texas, where the number of executions in the third millennium are almost double those at the Tower during its entire one thousand year history…

I’ve admitted my attachment to the legend of Bran is strong. It was reinforced on learning that Winston Churchill ordered more ravens for the Tower in the very year of my birth, after he was told only one raven had survived World War Two. Yet something in this modern story of ravens at the Tower of London grates on me. Unlike Sax and Parnell, I’m less interested in when the birds first arrived – when did ravens ever need a human invitation to appear in our garden – than why anybody alive today would think it OK to clip their wings?

A 2013 English newspaper carries a tale of two Tower ravens killed by a fox. With no apparent trace of irony, the item reports: “Fortunately there were two spare birds at the Tower to keep the numbers up. A spokesman for Historic Royal Palaces, the charity that cares for the birds, said it had been a ‘lucky escape’ because the hungry fox had almost taken the number of ravens below six.” http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2478131/Tower-London-ravens-snatched-fox-Security-increased-historic-palace-birds-killed.html#ixzz3UK7n0sFu

Tradition is one thing. But are Britain and her monarchy such fragile structures that, in the third millennium, they require people to capture and maim birds to keep them safe? If so, are such structures worth perpetuating? In the twenty-first century, who truly wishes to support a tradition that intentionally clips wings and limits free flight, whether avian or human?

I can’t feel in my bones that the Raven spirit who breathed life as Bran intended its dream of freedom from oppression for Britain to be applied this way. I’m certain the ravens in our garden wouldn’t appreciate having their wings clipped. Having watched how they can deal with a bird of prey many times their size, I would counsel strongly against the attempt.

Former Chief Justice, Sir Edward Coke, written about in Nights of the Road, spent nine months in the Tower of London from 27th December 1621 for annoying King James I. Coke’s grandson, Robert Wright/Villiers/Howard/Danvers, was confined there forty years later, after falling foul of Charles II.

Did either man watch wing-clipped ravens strutting in the grounds of their prison? I doubt it but, in my mind’s eye, I do see them both gazing out upon black birds swooping down from the many towers making up the prison complex to scavenge for whatever food they can find. And I sense both men watching and yearning for the same freedom such proud birds in flight embodied…

Maybe the real Unfortunate Disclosure of today is that the island of Britain will be free from oppression when we humans wake up to treat all species, including our own, with respect?