Talk of the Tower in last week’s blog set me musing about other London prisons in which some key 17th century real-life characters of Nights of the Road were detained.

My attention turned first to the prison where Frances Coke, Viscountess Purbeck, found herself confined briefly in 1635. Unlike the Tower, it has long since been torn down and so we are reliant entirely on historical descriptions and images for a record of what it was like.

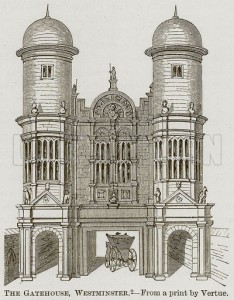

At the Gatehouse, which was originally the principal approach to a monastery which lay at the center of mediaeval London and which still retains symbolic importance today in the city and the nation as Westminster Abbey, two chambers above two arches first became prisons in the late fourteenth century. The Gatehouse has been described as ‘very massive, resembling a square tower of stone, and it altogether lacked the architectural decoration of the other gateways near King Street… Well might it seem gloomy, for it fulfilled the functions of a prison’.

The Abbot of the monastery reserved one of the chambers as a prison for convicted clergy or recusants awaiting sentence, while the Abbey’s cellarer, or butler, Walter Warfield, appointed the other chamber to become the public prison for Westminster.

The list of Gatehouse inmates includes many celebrated names and some-well known verses were composed there.

After sentencing in a trial in which the prosecution was led by Frances’s own father, Sir Edward Coke, Sir Walter Raleigh ‘was putt into a very uneasy and unconvenient lodging’ in the Gatehouse, where he spent his last night on earth. His wife visited him in the late evening, after which he wrote inside his Bible:

Ev’n such is Time, that takes on trust

Our youth, our joys, our all we have,

And pays us but with age and dust;

Who in the dark and silent grave,

When we have wander’d all our ways,

Shuts up the story of our days.

But from this earth, this grave, this dust,

The Lord shall raise me up, I trust.

Before being taken to the scaffold on October 29th 1618, just one year and one month after Frances had entered her own private prison of marriage, Raleigh is said to have eaten a hearty breakfast and, when asked if the cup of sack he was served was to his liking, responded wryly, “It is good drink if man might by tarry by it.” After reaching the scaffold in Old Palace Yard, his wit still did not desert him for, on sight of the executioner’s axe, he declared, “This is a sharp medicine, but it is a physician for all diseases and miseries.”

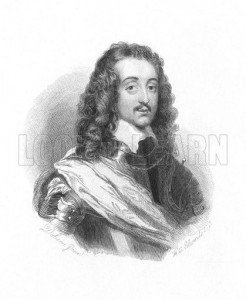

Almost seven years after Frances’s confinement, a Royalist colonel and poet, Richard Lovelace, presented a petition to Parliament requesting restoration of the Anglican bishops who had been excluded from the Long Parliament. For his pains, he was jailed in the Gatehouse for nearly two months, from late April until June 21st 1642.

Lovelace made good use of his time, including writing the following memorable lines ‘To Althea from Prison’:

Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an Hermitage.

If I have freedom in my love,

And in my soul am free,

Angels alone that soar above,

Enjoy such liberty.

Another celebrated 17th century figure who used his time in the Gatehouse to wield a pen was Samuel Pepys. Committed on June 25th 1690, on a charge of having sent information about the state of the English Navy to Royalists and the French Court, he was allowed out on bail at the end of July, on the grounds of ill health. Pepys used his time inside to put together materials for his ‘Memoirs of the Navy’, which were published later that same year.

During its early period as a prison, inmates did not usually remain for long at the Gatehouse, since they were typically awaiting sentencing or fulfillment of their sentence. Indeed, confinement as a type of punishment or means of correction generally figured as a much later concept in the English legal system.

In later centuries, the Gatehouse, like so many other London jails, became used as a debtors’ prison. Inmates were confined for forty days or until they could pay their debts or fines, but such a system was counterproductive, for prisoners had to pay for their keep during their incarceration, while being deprived of the liberty that might have enabled them to find the resources to pay. A box was let down to street level on a chain, in the hopes of attracting charitable contributions from passers-by, without which the poorest prisoners would not eat.

By the late 18th century the Gatehouse was in such a state of decay that it was pulled down, by an order of 1776, after a public campaign said to have been led by Samuel Johnson. By that time, other London debtors’ prisons were flourishing and they were also highly profitable affairs – at least for those who held the keys.

Frances’s lover, Sir Robert Howard, was confined in the Fleet Prison for three months before his family succeeded in getting him released, on payment of a bond of 2000 pounds and surety to the tune of an additional 1500 for personal appearance at court, within twenty-four hours of being called. He had been detained after refusing to plead in the Star Chamber and for also refusing to provide any information that would admit guilt or lead to recapture of the woman he adored.

Even had he been of a literary turn of mind, like Lovelace or Raleigh, Howard was reportedly denied ink, pen and paper during the three months of his detention, presumably to prevent him from communicating with Frances. Yet many inmates of the Fleet Prison could and did live in comparative comfort with pens, paper, books and even whole libraries – if they could pay for those comforts. Wardens were notorious for abusing their position, for which they had paid highly: at the end of the sixteenth century Sir Robert Tyrrel sold the Wardenship of the Fleet to Sir Henry Lello for 11,000 pounds (worth about $3.5 million today)

Fleet fees were the highest of any prison in England. During Elizabeth the First’s reign the following sums were paid:

Archbishop, Duke, Duchess: 21 pounds, 10 shillings per week for food (worth about $6,750 in today’s money) plus 3 pounds a week for wine ($945).

Yeoman: 1 pound, 14 shillings and 4 pence per week ($540) plus 5 shillings ($80) for wine

Poor: 7 shillings and 4 pence ($115).

Those without money were given a few minutes each day to beg at a grill overlooking the street.

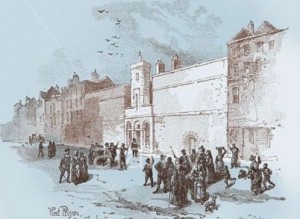

The Fleet was located on the east side of Farringdon Street in the City of London, beside the tributary of the Thames from which it took its name. The stream was originally navigable but also highly noxious, because of pollution flowing into it. The Earl of Surrey in the reign of Henry VIII described it as ‘a noisome prison, whose pestilential airs are not unlike to bring some alteration of health’.

The Fleet was also one of the most ancient prisons, having been named in the Domesday Survey. Until the mid-seventeenth century it was used primarily as a place of reception for Star Chamber prisoners. Anyone deemed a troublemaker for whatever reason by the Chamber, the Court of the Privy Council, could be sent to the Fleet without due process or appeal. Political prisoners, religious dissidents and anyone pronounced guilty of contempt ended up in the Fleet. Many notable figures were detained there.

In July 1641, not long after Howard’s detention and in part because of the long-running kind of abuses that he and others in his situation had suffered, an Act of Parliament was voted that abolished the Star Chamber. Thereafter, the Fleet became a debtor’s prison. It also quickly became notorious for one particular type of business: the shady Fleet marriages. In the century that followed as many as 50-60 couples per week were married in the Fleet ‘Chapel’. Crooked clergymen, themselves often in debt could hide in the Fleet and made a good living by performing the ceremonies which, being conducted in prison, were beyond the jurisdiction of the Church.

The thriving commerce in marriage expanded further over time, for a ‘sanctuary’ area developed beyond the prison gates, where debtors could live and move freely by paying additional fees to the wardens, and marriages could also be performed. But by now the Fleet was a very different prison from the one in which Sir Robert Howard had been detained, for that structure had been totally destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 on day three of the fire. The warden re-housed the prisoners in his own newly purchased house in Lambeth, and rebuilt the Fleet on its original site immediately at his own expense, which is sure evidence of how much he rated the value of his investment.

The Fleet was destroyed and rebuilt three times in its life before being closed and pulled down in the 1840’s, early in the reign of Victoria.

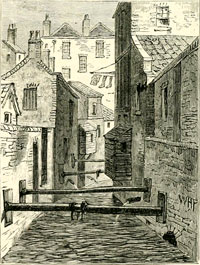

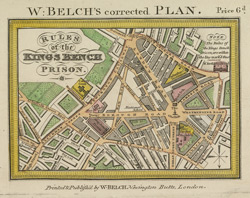

The Kings Bench is where John Clavell, of Nights of the Road fame, found himself incarcerated after being caught and convicted as a highwayman. This Southwark prison had existed from mediaeval times as two houses, the Angel and the Crane, in Angel Place, off Borough High Street. Further buildings were added in the reign of Henry the Eight, when a brick wall enclosed the whole.

The prison took its name from the court it originally served. As with the Gatehouse and the Fleet, it held political and religious prisoners and many literary dissenters, before becoming primarily a debtors’ prison in later centuries. As with the Fleet, inmate privileges could be bought at a price. The wealthy lived well and in comfortable rooms in the King’s Bench. They could have their family join them; they could entertain visitors, and might even live within three square miles of the prison gates, if they could grease the Keeper’s palm with sufficient silver, which bought them ‘Liberty of the Rules.’ Conditions for the poor, however, were squalid, for they lived in bare but filthy, overcrowded cells and were subject to violence, disease and starvation, unless they could find external supporters to pay for their food.

Charles Dickens has written extensively of prison life in David Copperfield, Nicholas Nickleby and Little Dorrit. He also wrote of the Fleet in Pickwick Papers. In doing so, the author had personal experience to draw on: in February 1824 his father, John Dickens, was imprisoned in the Marshalsea for failure to repay a debt of forty pounds and ten shillings, after having lost his job in the navy pay office.

While the rest of the family moved to join John in prison by the end of March, twelve-year-old Charles tried to raise money to clear the debt. He walked four miles to and from lodgings in Camden Town each day to work at a factory at Hungerford Market. He visited his family in the Marshalsea on Sundays.

John Dickens eventually regained his freedom by declaring insolvency on 28 May 1842 and agreeing to settle all his debts at a later date. Of this difficult time, Charles Dickens would later write: ‘my whole nature was so penetrated with grief and humiliation…that even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life.’

As with the Dickens family in nineteenth-century London, Frances Purbeck, Sir Robert Howard and John Clavell all succeeded in leaving behind the London jail in which they had been incarcerated in the seventeenth century. They were among the fortunate ones of their time, since many died of gaol fever while detained, or left to face execution or transportation. Yet all three were marked by their prison experiences, albeit in different ways and to different degrees.