As news of an audacious Easter weekend robbery percolates Hollywood, scriptwriters scour the media for details, hoping to be first out with “The Greatest Hatton Garden Heist Story Ever Told”.

Meantime, I sit reflecting on the extraordinary history of this quarter of London that provided a backdrop to my time-slip novel, Nights of the Road. Its seventeenth century heroine, Frances Coke, was almost certainly born at Hatton House, whose once magnificent gardens are the present-day site of one of the world’s great jewelry districts and its most recent drama.

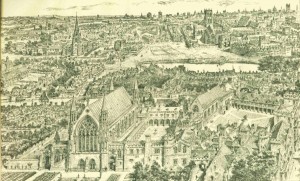

The great house lay in an ancient complex, named Ely Place after John de Kirkeby had bequeathed ‘a messauge and nine cottages’ in 1290 to future Bishops of Ely, to make a London home worthy of their status. These ecclesiastics occupied powerful positions in mediaeval England, and the palace they built matched any in the capital. Situated on open ground, its garden alone occupied fifty-eight acres of orchards, hay meadows, strawberry fields, vineyards, formally laid out terraces and lawns, with decorative fountains and ponds.

John of Gaunt removed to Ely Place after Wat Tyler torched his palace. He died there in 1391, and it is at Ely Place that Shakespeare has him declaiming famous lines in Richard II:

This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea…

(Watch the YouTube below for four magnificent renderings of John of Gaunt’s speech)

Ely Place saw many grandiose dramas and masques. Sergeants-at-Law used the seventy-four-foot-long hall with its great Gothic windows for banquets that could last for days. Monarchs and foreign ambassadors regularly attended. Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon hosted simultaneous and separate banquets at the palace for the Lord Mayor and City dignitaries on the first of a five-day feast in 1531. Divorce proceedings were already underway against the unhappy queen, who was making her last state appearance…

Fruit from the garden is mentioned in the Bard’s Richard III: “My Lord of Ely. When I was last in Holborn, I saw good strawberries in your garden there. I do beseech you, send for some of them,” says the Duke of Gloucester, on a day he will commit murder.

Garden produce figures more peacefully in the lease of Hatton House, as part of the palace was known, by the time Frances Coke’s mother, Lady Elizabeth Hatton, inherited.

Her predecessor, Sir Christopher Hatton, had been Lord Chancellor to Elizabeth I. Courtier and Queen may have enjoyed a more intimate relationship. Certainly she appreciated her nimble-footed dancing partner enough to grant him a lease on the Ely Place gatehouse, excluding two rooms to be kept for the Bishops’ prisoners, while awaiting trial and sentence. He also received the first courtyard, the long gallery, with its rooms above and below, the stables and fourteen acres of garden and orchard.

The Queen decreed an annual rent due on Midsummer Day of one red rose for the gatehouse and gardens, and for the remainder just £10 and ten loads of hay. The Bishop of Ely resented such a capricious rent, arrived at without consulting him. He also complained at having to repay Sir Christopher for expensive improvements. The Queen responded by threatening to unfrock the Bishop. The prelate received a sop of free access for himself and his successors through the gatehouse and the right to gather twenty bushels of roses from the garden annually.

Sir Christopher extended Hatton House by buying up neighboring tenements and continuing lavish refurbishments, on borrowed money. He had other building programs and, at his death in 1591, he owed his Queen over £42,000. She mourned his passing, but monarchy also expected its money back, which created financial headaches for his heirs.

Hatton never married, unless in secret to avoid a jealous sovereign’s wrath. When he died, Hatton House was settled on his nephew, William Newport, who took the Hatton name. William had little time to enjoy the property, which his young widow Elizabeth inherited in 1597, along with Corfe Castle and manors throughout the land.

Other relatives made claims but Lady Hatton married again quickly, so they faced the country’s premier lawyer, Sir Edward Coke, as well as Elizabeth, who never shied away from a challenge and issued many of her own. Over the years, she engaged in numerous public wrangles relating to Hatton House. They included fights with her second husband, upon whom she eventually shut her door.

Elizabeth remained Lady Hatton by refusing to take Coke’s name. After one major skirmish, she wrote: ” Sir Edward broke into Hatton House, secured my coach and coach-horses, nay, my apparel, which he detains; thrusts all my servants out of doors without wages; sent down his men to Corfe to inventory, seize, ship, and carry away all the goods, which being refused him by the castle-keeper, he threats to bring your lordship’s warrant for the performance thereof. But your lordship established that he should have the use of the goods only during his life, in such houses as the same appertained, without meaning, I hope, of depriving me of such use, being goods I brought at my marriage, or bought with the money I spared from my allowances. Stop, then, his high tyrannical courses; for I have suffered beyond the measure of any wife, mother, nay of any ordinary woman in this kingdom, without respect to my father, my birth, my fortunes, with which I have so highly raised him.”

The Spanish Ambassador Gondomar, leasing another part of Ely Place, evidently felt sympathy with Sir Edward even while flirting with his wife. A gossip wrote: “he could do no good upon the Lady Hatton, whom he desired lately, that in regard he was her next-door neighbour, he might have the benefit of the back-gate to go abroad into the fields, but she put him off with a compliment; whereupon, in a private audience with the King, among other passages of merriment he told him, that my Lady Hatton was a strange lady, for she would not suffer her husband, Sir Edward Coke, to come in at her fore-door, nor him to go out at her back-door.”

Elizabeth lived large, entertained extravagantly and frequently mismanaged money. Having decided to divest herself of Hatton House in the 1620’s, to another wealthy widow, she made such complaint about the deal struck, that the Duchess of Richmond handed the house back and demanded repayment of all costs incurred.

Ordered in writing by King Charles I to hand £4,000 to the Duchess, Elizabeth responded: “I humbly decline the order made by the Lords Referees, and beseech your Majesty to refer her Grace’s cause and mine to your Majesty’s laws or courts of equity, notwithstanding the overmatching advantage her Grace hath in purse, in friends, and in favour of the times over my misfortunes… The four thousand pounds mentioned in your Majesty’s letters I am so far from that ability to satisfy as both my lands and friends are engaged for my ordinary sustenance, neither having any maintenance from my husband Sir Edward Coke nor any part of my jointure from Sir William Hatton.”

The case went to court. Elizabeth was fined over £6,000. She ignored the ruling. The Duchess died in 1639, with the fine unpaid…

National Archive documents show that both Coke and Lady Hatton engaged in transactions to sell, assign and lease all or parts of Hatton House at different times, yet the property always reverted to Elizabeth in her lifetime. She leased rooms for a nominal one penny a year to Alderman James Bellew in 1644, when Parliament, whom she supported in the Civil War, re-affirmed her ownership. In that same year, we find Elizabeth in dispute again, this time petitioning to oblige Thomas Johnson, a carpenter in Shoe Lane, “to pluck down what he has already erected”: foundations for an ale house at the north-east end of Hatton House Garden.

When Elizabeth died in January 1646, her grandson and heir – Robin of Nights of the Road – elected to sell. Deeds of May 1648 indicate that Robert Villiers sold Hatton House to Edward, Lord Montagu of Broughton. It went to Edward’s daughter, another Elizabeth, who married – a Sir Christopher Hatton! Hatton House had come full circle.

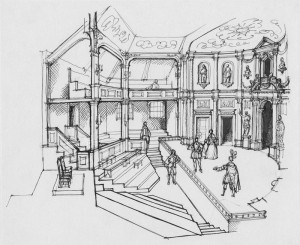

Lord Hatton, a Royalist ennobled by King Charles, absented himself from England during the Interregnum, leaving his wife at home in Northampton to manage their affairs. Hatton House suffered neglect and decline in the Commonwealth, having been requisitioned again as a prison and then as a hospital ‘for maimed soldiers’. The Kingdom’s Weekly Intelligencer reported that soldiers raided several theatres in London on January 1 1649. Some of the troupes were allowed to retain their costumes, but the King’s Men caused trouble so had theirs confiscated. “They made some resistance at the Cockpit in Drury Lane.”

Historia Histrionica recorded that the soldiers “carried ‘em away in their habits, not admitting them to Shift, to Hatton-house then a Prison, where having detain’d them sometime, they Plunder’d them of their Cloths.”

In the 1650’s, the hospital ordered Lady Hatton to restore rooms occupied by the family for hospital use, and complained of disturbances caused by horses in the adjoining Hatton stables.

Days of grandeur and fine living at Hatton House were done.

Then a new chapter began. In the year before the Restoration, on June 7 1659, diarist John Evelyn reported ‘foundations now laying for a long streete and buildings on Hatton Garden designed for a little towne lately an ample garden’. Construction proceeded apace, although green spaces and quiet corners could still be found. Bishops of Ely came back and restored their ancient chapel, St Ethelreda’s.

With its new houses, the quarter became a desirable residential location for people conducting business in Parliament, the Law Courts and the City. In 1703, a great granddaughter of Lady Hatton and daughter of Robin married wealthy Sir William Wogan from Pembrokeshire, whose smart London address was Hatton Garden.

When the last Lord Hatton died, the Hatton property reverted to the Crown and this time the Bishop of Ely felt satisfied with the arrangement. The see transferred all its rights to Ely Place in return for a fine house in Piccadilly and an annuity of £200 in perpetuity.

Commerce gradually overtook Hatton Garden, as many seventeenth-century tokens of the area testify, but two more centuries elapsed before gold, platinum and diamond merchants and jewelers invaded Hatton Garden en masse.

With them came the risk of heists. On November 18 1881, the Daily Telegraph reported: “A most daring and impudent robbery was committed on Wednesday evening at the branch post office in Hatton Garden, London. About 5 o’clock, as one of the officials had just made up the country mails in two bags, one containing the ordinary mail bags and the other the registered letters some of which contained jewelry and diamonds to a very considerable amount, the gas in the building was suddenly turned off at the meter, plunging the place into total darkness. In the confusion and commotion which ensued among the assistants and the customers in the office, a man made his way to where the bags, already made up, were hanging on their customary hooks, awaiting the arrival of the mail cart which conveys them to the General Post Office, and seizing the bags, rushed out of the door.”

Stolen valuables, estimated at only £100,000, were many times less than the latest haul, but a huge sum for 1881. One paper predicted gleefully that arrests were unlikely, since tracing uncut diamonds was like trying to identify “uncooked haricot beans”. Yet guilty men and women were arrested in Belgium and Paris by March 1882.

No haricot beans appear in today’s Guardian headline for the latest robbery: Cops and ex-robbers on Hatton Garden heist: ‘This is no bunch of mugs’.

Anyone feel like predicting when arrests may be made?