Naively, I asssumed Nights of the Road would gallop off into the distance once published, leaving me free to dig again into the delights of the eighteenth century for my Corsican trilogy. But the seventeenth century has not done with me. Nor have certain characters from Nights of the Road, who were still standing after Frances Coke made her exit and Sarah James tripped the light fantastic at a Hollywood Bowl after-party.

Villain or Victim: Lord Purbeck Reconsidered

When I first met the man that the young heiress Frances Coke did not want to marry, I assumed it would be simple to paint John Villiers, Lord Purbeck, as unappealing husband. Gossips labeled him lunatic, subject to melancholy and manic episodes that could harm him and others. Reports of the day recorded incidents as John Villiers was removed temporarily from Court and his role as Keeper of the Prince’s Palace. Add his toxic family to the mix, and it became easy to empathize with a high-spirited teenager who, dreamed of marrying for love, but was forced to take twenty-six year old Villiers as spouse.

My soft spot for John developed from the day I read that he cared tenderly for Frances when she became seriously ill, only months after she had born another man’s child. “The lady Purbecke is sick of the small pox and her husband is so kind that he stirs not from her bed’s feet,” wrote John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton, just before Christmas in 1624.

Everything I have read by Chamberlain and others suggests that Purbeck adored his young wife and wanted the best for her. He appeared less preoccupied with the size of her dowry than his avaricious relatives although, having declared to her father his willingness to have taken Frances “in her smock”, he somewhat diluted the effect by adding – perhaps at his mother’s insistence? – that he “should be glad by way of curiosity to know how much could be assured by way of marriage settlement upon her and her issue.” I’ve uncovered no record of Purbeck speaking negatively about Frances, during their years together or apart. He refused to denounce his wife publicly during her adultery trial in 1625.

Years after the trial Purbeck reportedly gave his signature to a document declaring that he did not wish to accord Frances privilege as a peer’s wife, which would have exempted her from serving her sentence. Did he act from a sense of having been betrayed, or did a brother with an ulterior motive maneuver him into signing, even forge his signature without his knowledge? Given Purbeck and Buckingham’s overall conduct, I incline toward the latter more than the former.

Virgo Man

For, by the time I had pieced together such ‘facts’ as I could unearth, including that John Villiers shared a birthday with my grandfather, I began to feel I knew Viscount Purbeck well. Much of what I saw I liked. Born at noon on the 6th September 1591 in Goadby, Leicestershire, John Villiers’ described behavior reveals many hallmarks of a Virgo temperament! Of course he would have looked after Frances when sick, and always supported her loyally, wouldn’t he? I’ve known enough Virgo men, professionally as well as up close and personal, among work colleagues, family and friends, to agree with my Russian daughter-in-law who calls them “good husband material.” She should know: she married one.

Of course George Villiers was willing to delegate affairs of state to his elder brother. What safer hands could he wish for? “The Lord of Buckingham is so oppressed with multiplicity of business that he puts over a great part to his brother Purbecke and (as I heare) referres all suitors to him to come in by that door,” writes Chamberlain in 1720. And George relied on those diligent hands often thereafter, when he was off creating havoc in Spain with Prince Charles, or wooing the Queen of France and stirring up war.

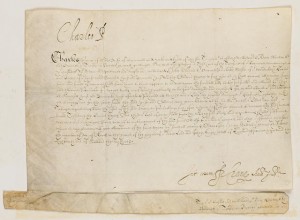

Of course the Prince of Wales relied on Purbeck to administer his Palace. The following 1620 signed manuscript from the Enys Collection – which fetched more than $2,500 at auction in 2004 – is an example affirming that Charles trusted Purbeck with the funds to pay wages at Denmark (aka Somerset) House:

It’s no surprise that a man born under the aesthetic sensibilities of Virgo should display a cultured and artistic disposition alongside practical common sense. Purbeck took a prominent part in many Court masques. He enjoyed close relations with the talented Lanier family of composers and musicians. He was also instrumental in bringing the painter Antony van Dyck to England.

If not quite equal to the ‘angelic’ Steenie in looks and manufactured charm, close study of the family group painted in 1628 and held in the Queen’s Royal Collection shows John Villiers as a man of pleasing appearance.

© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: The Royal Collection

© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: The Royal Collection

In the portrait above, Purbeck is shown standing at the right of his mother the Countess of Buckingham, while Kit Villiers, Earl of Anglesey stands to her left and George, Duke of Buckingham is seated.

At least one person of the time considered John Villiers the most appealing member of his family. It was said, “Only his brother, Purbeck, had more wit and honesty than all the kindred beside and did keep him (Buckingham) in some bounds of honesty and modesty, whilst he lived about him, & would speake plaine English to him.”

In spite of that plain English, John Villiers could not protect his wife from persecution. Too often for his and her good, he allowed his wishes to be overridden, to the point that he was banished to the country and Frances was caste out on the street. As a sibling and son who preferred to protect and please those he loved, Purbeck must have been handicapped when faced with an unscrupulous brother and scheming mother. It took such worthy opponents from her own generation and sex as Lady Hatton and the Countess of Suffolk, themselves no strangers to manipulation and string-pulling, to serve the formidable Countess of Buckingham in her own currency.

One man who knew more than most about Viscount Purbeck considered the mother a serious obstacle to his peace of mind. John’s unpredictable episodes of mania and melancholy created fear, in an era when people still scratched their heads to understand, let alone successfully treat, symptoms that today would be labeled ‘bi-polar.’ The Villiers family turned for help to Richard Napier.

17th Century Medicine: A Man in the Cusp between Two Eras

Napier was an unusual character, who would probably have felt far more at home among holistic health practitioners of our times than the medical men who came after him. One more way in which the seventeenth century echoes curiously down into our twenty-first.

Born on what Michael MacDonald called “the cusp between two eras dominated by the antagonistic forces of magic and science”, Napier was one of the last to immerse himself in the Renaissance magi tradition of Dr John Dee, yet he also simultaneously became ordained as an orthodox and conventional Anglican minister.

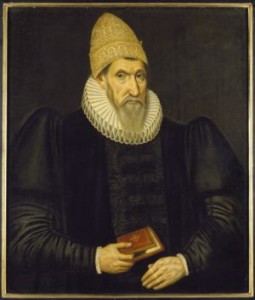

Respected alike by alchemists and mathematicians who revered his mastery of astrology, chemistry and magic secrets, and those many theologians of the day who consulted him for his erudition in religious affairs, Napier’s standing among his contemporaries seems to have been high and, in a suspicious age, he avoided prosecution for magical arts. His portrait shows him shy, stern and scholarly:

©Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Napier (1559-1634) died early enough to avoid any Puritan oppression in the Civil War, but his terror of preaching may have been fueled by his fear of being a target for extremists. That terror led him to employ a curate to deliver his sermons, while he devoted his time to patients. Of these there were thousands, for Napier’s reputation spread far. He saw between five and fifteen patients a day and more than ten thousand over the forty years of his practice.

Reputedly Napier preferred treating the poor to the rich. He was cautiously flattered when his brother opened doors to noble friendships and he duly enjoyed the honor of kissing the hand of the King and Prince Charles. But he found Buckingham “full of bribery” and loathed the Countess. Napier resisted the family’s pressure to give him Purbeck as patient, but received him for extended periods in 1622, 1624 and 1631.

The Casebooks Project

How did Napier treat the wide range of medical and psychological symptoms with which he was presented in general? By asking questions; by ascertaining and mapping his patients’ identity against the position of the planets and signs in the heavens; by listing the detailed manifestations of their disease, and then matching and proposing medical and/or celestial remedies.

Certain remedies were conventional for the day: purging, vomits, bleeding, soothing concoctions of egg white and milk, herbal potions to relieve pain and aid sleep. But Napier was also a ‘talking doctor’. To some he offered confidential healing sessions. To others he offered magical amulets. He is reported as giving particular heed to the motions of Saturn when his patients were in their manic phase. He noted down all in great detail and painstakingly searched for behavioral patterns over the years. An empirical scientist as well as a man of faith.

How did Napier treat Purbeck in particular? I don’t know! Which is why I am eager that a ten-year Cambridge University research project due to complete in 2017 should yield all its results online. Napier’s cases from 1597-1615 are already accessible at The Casebooks Project www.magicandmedicine.hps.cam.ac.uk. I’m hoping Purbeck’s notes for 1622 will soon appear.

I sit and sift shells, with Nights of the Road done and dusted, still searching for answers to unanswered questions about Lord Purbeck. I want to know what light the Napier case notes may yield. I’m curious about Purbeck’s second marriage and his relations with the young man he formally acknowledged as heir for years, then of whom he made no acknowledgment in his will. In the course of ‘knowing him’, I have several times revised my perspective on John Villiers. Perhaps more surprises are in store.

Many of his contemporaries misjudged him, including the man forever sending juicy tidbits to Dudley Carleton. On November 29th 1617, John Chamberlain wrote acerbically, “He (John Villiers) is accounted a weak man and not long-lived, so there needed not so much ado to get him a wife.” Purbeck may not have equaled Chamberlain’s seventy-five year lifespan, but he notched up two marriages and a creditable sixty-seven years, which greatly exceeded the odds in a century when life expectancy was still under forty.

More later…. Meanwhile I hope you enjoy this charming animated introduction to The Casebooks Project:

The Casebooks Project from Beakus on Vimeo.