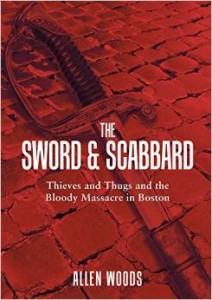

Last week I reviewed the historical novel, The Sword and Scabbard, set in eighteenth-century Boston on the eve of the American Revolution and War of Independence. This week it is my pleasure to share with you my interview with the book’s author, Allen Woods.

Allen has been a freelance writer and editor for nearly three decades, and The Sword and Scabbard is his first historical novel.

Welcome to Midi’s Blog, Allen!

Have you long been a reader of historical fiction? If so, what have been some of your personal favorites?

AW: I have read more crime novels and mysteries than historical fiction, but recently have greatly enjoyed books that are both. I consider Elmore Leonard one of the greatest crime novelists, using characters and dialogue that are unmatched. One my favorites is a crime novel set in the 1930s called The Hot Kid. I also felt the Civil War novel and movie Cold Mountain was a superb combination of character and context. David Liss offered an interesting view of America and its criminal and political side just after the Revolution in The Whiskey Rebels.

You clearly have a detailed knowledge of events in the period of which you write, and of the geography of Boston itself. What made you decide to write about this particular time and why a novel rather than a history of the period?

AW: There is a great deal of mythology in the U.S. surrounding the Revolutionary era. Living near Boston, I began to learn more from some direct sources, and eventually had my eyes opened about many of the events and people of this period. It is also a pivotal period in U.S. and world history, with both great and wretched deeds very common. Fiction seemed by far the best way to approach the period and subjects. I’m not sure I have the skill to make straight historical writing interesting.

Why choose a protagonist of British birth?

AW: I knew the novel would be revolve around the Boston docks and that smuggling would be a central activity, since it played such a large role in American business and in the conflicts between Americans and British Customs at the time. In imagining a central character who would be involved with smuggling on the docks, a British Navy deserter seemed a natural choice. His history came about naturally from there.

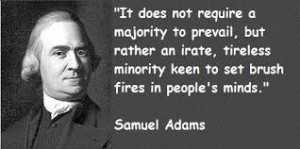

What is your own view of the Sons of Liberty and, in particular, of Samuel Adams?

AW: I believe that Samuel Adams may have been the best community organizer in history, constantly able to gauge the varying factions within the American movement to direct them toward his goals. I also believe that he was probably one of the more altruistic of the patriots, given that he had little money to begin with and never gained any through his political work. At the same time, he held a deep grudge against the British for their persecution of his father who had the temerity to attempt to start a bank to serve American interests. I believe that, like many politicians, he was willing to sacrifice lives and make unsavory political deals to pursue his Revolutionary dream.

I am looking forward to doing more in-depth research on individuals in the Sons of Liberty, but during this period, it was the hard men in the street that accomplished Revolutionary goals. There were the thinkers and then the foot soldiers, and many of the foot soldiers, like some of those killed in the Massacre, were spoiling for a fight and weren’t that particular who it was against. Many had been abused at the hands of British sea captains or pressed into the Navy or simply saw the British lords as arrogant and greedy and were happy to break some windows and break some heads. I believe that the cause of freedom offered them a ready and satisfying outlet for their anger.

How accurately do you think the recent History Channel series, Sons of Liberty, portrayed events and characters?

AW: I’m not usually one to rant, but their effort tipped me over the edge. I was very excited about the coverage of the period and the publicity it might bring, especially since it was by a respected (I thought) media outlet. I walked out of the room fuming after the very first scene and continued muttering and cursing throughout the first episode. The next day I posted comments on their Facebook page suggesting that they change their name to the Fantasy Channel and listing several reasons why. The post quickly disappeared.![]()

They began by turning Samuel Adams into a young, virile action figure, jumping across Boston rooftops to evade British capture in a completely fictitious scene. They also showed him clubbing a British soldier to the ground after the Boston Massacre, an event that is beyond ludicrous given how carefully events were documented at the time and soon afterward. Samuel Adams was over forty at the time, almost frail with a palsy in one arm. There was never ANY indication that he took direct physical action against any soldier or any other enemy.

Their portrayal of smuggling Hancock’s wine in small bottles was also ridiculous, since the wine was transported in barrels called pipes that held over 100 gallons. I could go on and on, but I thought it almost criminal that they changed extremely interesting factual events at a whim. All historical fiction uses some artistic license (that’s why it’s called fiction) but they should be prohibited from using the word “historical” in any reference to their work. They used names and the broadest of event outlines to create a story they thought would fit popular sensibilities. As you can see, I’m still disturbed by it.

How much of your own character and story is embedded in your novel?

AW: There are similarities between Nicholas Gray and myself, something I think happens naturally in fiction. Like Nicholas, I lost my parents fairly early and spent some formative years rattling about and learning to fend for myself in some city streets and near the boundary between legal and illegal acts. It was also a time of great political and social turmoil because of the Vietnam War and the great cultural divides of the time. I was firmly against the War but also found that the ideals and methods used in political opposition weren’t always the most pure. I ended with a healthy suspicion of high-minded and idealistic rhetoric, something Nicholas shows on many occasions.

What did you most enjoy while writing the novel?

AW: I really enjoyed writing the dialogue. It was a rare time when I could hear voices in my head and make them useful. In most cases, it came fairly easily.

What did you find most difficult to write?

AW: I struggled with the opening, knowing that there needed to be a strong hook. However the story itself is best told chronologically, I think, so focusing on an exciting opening while filling in the background took a lot of work.

“MY PROBLEMS with Ezekiel Tobin began in 1766, during the time the British still thought they might collect money from the tax stamps they ordered Americans to buy before they could legally sell everything from paper to glass. It was just a few months after I first took a room above the Sword and Scabbard tavern, so that I could serve the drinks and tend the crowd for the Widow Maggie Magowan.” (Excerpt From: Allen Woods. “The Sword and Scabbard: Thieves and Thugs and the Bloody Massacre In Boston.”)

If you would do or write anything differently, given what you know now, what would it be?

AW: The decision to self-publish is a tough one with the industry itself in what I consider chaos in terms of pricing, distribution, publicity, and control by Amazon. But I’m not really sure what other choices I might have made.

If you had lived in that time and place, where would your own political allegiance have lain?

AW: There’s no doubt I would have been one of the Sons of Liberty, fighting against the British lords and Customs. But I might have been a little skeptical of some of the actions taken by the Revolutionary leaders, such as their selective enforcement of the non-importation agreement to favor larger merchants.

What parallels, if any, do you observe between pre‐Revolutionary Boston and events/perspectives in the world today?

AW: The struggle to control information and the media is very similar today to what it was back then. Media outlets such as Fox News and MSNBC in the U.S. provide extremely slanted coverage of news events while claiming that they are providing a fair approach. Samuel Adams did the same, continually inciting Americans against the British with either questionable or completely false information. The Sons of Liberty also physically destroyed an opposition newspaper and forced its owner to flee in disguise after he continued to publish facts about the non-importation agreement.

The American merchant class was also able to convince the people on the street that actions which threatened the merchants’ profits, such as payments to Customs and a variety of taxes, were harmful to everyone else, even though average people were never going to pay any tax themselves. In the U.S. today, many poor people have been convinced that actions that support greater business profits for owners are in their own best interest as well.

In my mind, the struggle for money and power during Revolutionary and modern times is very much the same.

What are your hopes and aspirations for The Sword and the Scabbard?

AW: I would like to devote myself to writing historical fiction full-time. If The Sword could provide an opportunity for that, I would be very happy. I would also like to see it provoke a bit more debate and discussion within the historical community about the mythology surrounding the Revolutionary movement in the U.S. The 250th anniversaries of important events are approaching and I would like to see some more realistic coverage of them.

In some ways it feels by the end of the novel as if the real action for the country and the book’s characters may be just beginning. Is The Sword and Scabbard essentially a scene setter for another book set in the thick of the Revolutionary War? If so, what kind of book will that be? What characters will we meet?

AW: I plan to write one or more books in a series that features Nicholas and Maggie now that they are established in Boston. I don’t have exact plots, but all the action of the Tea Party, the resulting occupation of Boston, and the events of the war and later remain in their future. I would expect that fascinating historical figures such as Paul Revere, Dr. Joseph Warren, Benedict Arnold, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington will all be featured. There is also a possibility that the plots may involve mysteries or scandals that Nicholas may need to help resolve.

Based on your own experience, what recommendations do you have for someone wishing to write a debut historical novel?

AW: Choose a period you’re fascinated by and do enough research so that when you begin to write, you feel that you’re living in that period. The history should be a sidelight to the story, occurring as natural explanations of its context.

What question would you have liked, that I have not asked you?

AW: None that I can think of now.

Thank you for your time, Allen, and good luck with The Sword and Scabbard!

You can purchase The Sword and Scabbard direct from Allen Woods’ website at: http://www.theswordandscabbard.com or at Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Sword-Scabbard-Thieves-Bloody-Massacre/dp/0990884104/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1433197306&sr=1-1&keywords=The+Sword+and+Scabbard