And now for something completely different, which takes us away from the seventeenth century for a week.

A few days ago, a Google Doodle caught my attention.

Clicking it took me to the 133rd birthday of a woman mathematician. I had never heard of her and I wasn’t the only one, it seems, for Emmy Noether was little known in her lifetime. Yet, among many other tributes, she once received a rave write-up from Albert Einstein and she even has had a crater on the moon named after her.

There’s no need to say anything more here about Emmy Noether. If you missed it, Google did a great job of writing about her, and also spurred Vox and the Washington Post to produce interesting biographical pieces. https://www.google.com/doodles/emmy-noethers-133rd-birthday ; http://tinyurl.com/nlgdxyc

Instead, I do want to tell you about some other women who’ve been important in my life, including the one of whom Emmy instantly reminded me. For, when Einstein wrote effusively in a letter about the redoubtable German, Emmy Noether, and said, “However inconspicuously the life of these [academic] individuals runs its course, nonetheless the fruits of their endeavors are the most valuable contributions which one generation can make to its successors”, he might as easily have been writing about Dame Mary Lucy Cartwright, born twenty-six years after Emmy, in England at the turn of the twentieth century.

I first met Dame Cartwright on a sunny and crisp October day in the Sixties. By then she had been Mistress of Girton College for almost as long as I had been alive. Ours must have seemed to her like just one in a long stream of young women ‘fresher’ undergraduate small groups invited to take tea in her college rooms when we first ‘came up’ to university.

I first met Dame Cartwright on a sunny and crisp October day in the Sixties. By then she had been Mistress of Girton College for almost as long as I had been alive. Ours must have seemed to her like just one in a long stream of young women ‘fresher’ undergraduate small groups invited to take tea in her college rooms when we first ‘came up’ to university.

Fear that my inadequacies would be found out across the bone china teacups and ginger biscuits led me to babble when spoken to directly, and to ask many more questions than may have been polite to ask of one’s Mistress over afternoon tea. I must have seemed to my seniors like a chick just out of the egg, for I had no context for this new world I had entered and everything about undergraduate life was strange to me. I was convinced, as I would remain for most of my six years there as undergraduate and graduate student, that I had been accepted at Cambridge ‘by mistake’ and somehow got in under false pretences.

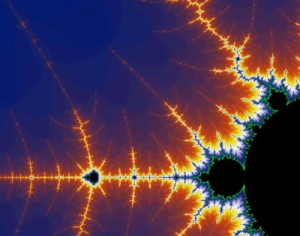

In truth I babbled also because I was awestruck. What did one ask a woman reputed to be one of the great mathematical minds of the world? I had given up mathematics, with a huge sigh of relief, at the age of fourteen after scraping a B in GCSE, so asking intelligent questions about awkward differential equations was way above my student pay grade. Unfortunately, I was also still many years away from becoming abidingly fascinated by chaos theory, for which Dame Cartwright’s work with J.E. Littlewood would lay a groundbreaking foundation.

But the lean and iron-gray-haired woman who twinkled at us over the teacups on that October day was both approachable and memorably modest. I did have some inkling, thanks to gossip along college corridors on our way up to her rooms, that our Mistress was famous for having done something terribly important during the war to do with radar. I was curious to learn more and wondered aloud if she would be willing to explain it.

One of Mary Cartwright’s most appealing characteristics was her total lack of interest in touting her own achievements. Maybe it was her natural humility on that day or perhaps she was still bound by an Official Secrets Act, which prevented her explaining just how she had contributed to the wartime defense of Britain against enemy air attack, and in the process laid the basis for an entirely new field of science. Whatever the reason, she made light of all she had done, and soon turned the questioning around to ask us about our hopes and aspirations for our time at Cambridge. But not before responding to my question with an answer that has stayed with me through the years.

She declared her personal conviction that the most valuable work she had done as part of the war effort was to pack parachutes for the men who would be dropped into enemy territory. Her eyes shone as she explained that it had been extremely enjoyable too. For, while undertaking this vital yet simple, mundane and repetitive task with her hands, she had enjoyed both an immediate reward of feeling useful to her country, and also the freedom to allow her mind to range far and wide over any mathematical problems that might be pre-occupying her in the moment.

As she was speaking, I felt an instant kinship with the Mistress, for I had always felt liberated to reflect and think wide and deep whenever my own hands were engaged repetitively in simple tasks, like knitting squares for charity blankets. Yet I also knew then, as I know now, that my own mental wanderings fall short of scaling the academic heights that extraordinary women like Emmy Noether and Mary Cartwright achieved. That they did so when sexism in science and seats of learning was even greater than in my day seems admirable.

Another woman who has had a profound effect upon my life was my geography ‘Director of Studies’. Dr. Jean Grove was a glaciologist, who became interested in climate change before the world woke up to the issue. She reconstructed, over the course of many years of painstaking fieldwork, the history of glacial fluctuations over 1,000 years. Her seminal book, The Little Ice Age, was published in the Eighties. Long before alarm bells began sounding more widely, Jean was pointing to the potentially dire consequences of even minor climate changes, and backing it up with data and evidence, through having exhaustively tracked and presented what happened in the mediaeval warm period and the Little Ice Age.

Jean’s erudition might easily have been overwhelming to a country girl from a grammar school that had only sent one boy to Oxford and no girls to university in the three hundred years since being founded by a wealthy Grocer. But Jean herself never allowed that to happen. Like Mary Cartwright, she made light of her own achievements. She was also quite simply one of the kindest, most human teachers I have encountered. Her round face glowed, her smile was dazzling and her laugh so infectious and frequent that just spending time in her presence was a tonic.

Jean married a fellow geographer, Dick. The Groves’ home was a warm and welcoming haven whenever east winds blew cold across the Fens. The house was usually full and it rarely was clear who belonged there and who, like me, was just passing through. A mother of six and intensely practical as well as academically brilliant, Jean could spot student blues at a thousand paces. She also seemed to have that remarkable sixth sense which enabled her to gauge if tea and sympathy were the best medicine in the moment, or whether she should administer a humorous-but-no-nonsense recommendation to pull one’s finger out.

Jean married a fellow geographer, Dick. The Groves’ home was a warm and welcoming haven whenever east winds blew cold across the Fens. The house was usually full and it rarely was clear who belonged there and who, like me, was just passing through. A mother of six and intensely practical as well as academically brilliant, Jean could spot student blues at a thousand paces. She also seemed to have that remarkable sixth sense which enabled her to gauge if tea and sympathy were the best medicine in the moment, or whether she should administer a humorous-but-no-nonsense recommendation to pull one’s finger out.

Jean was fulsome in her pleasure and congratulations, while others pursed their lips or muttered about not mixing marriage with studenthood, when I showed off a sparkly new engagement ring at the end of my first year. And Jean shared my elation, when I told her of my pregnancy at the end of my second year. At the time, other dons at my College were debating whether or not I should be allowed to continue my studies once I became a mother…

Jean Grove had excellent advice to offer on how to deal with morning sickness, since she had suffered in her turn. It was at her suggestion that I took a year out to enjoy the first year of my son Mark’s life, before returning to complete my degree when he was a year old. From then on, Mark was as welcome as me at 8 Storey’s Way and, while I discussed my latest essay with Jean, he joined Lucy or William or Jonathan in scrambling and scampering happily around the house.

When I graduated and embarked on what I assumed would, for some years, be the role of full time wife and mother, only to find that my military husband had been sent off on a nine-month unaccompanied posting and my two-year-old son, so well socialized by now among the Grove children, preferred the company of kids at nursery school to staying home and playing with Mum, it was Jean who met me on a Cambridge street corner, took one look and asked “Whatever is wrong?” After she had heard my tale of woe, she wasted no time in sympathy but instead opened the door to an interesting research assistantship job, which led quickly to another and ultimately to me registering to study for a research degree.

I was not the only student to feel greatly benefited and blessed by being taught and sponsored by Jean Grove at a formative stage of my life.

Sylvia Ann Hewlett is a high profile business thinker, well known on both sides of the Atlantic, who has focused much of her career on professional challenges faced by women and minority groups. Sylvia is my age and was my contemporary at Cambridge. Daughter of a mining family from the Welsh valleys, who also attended a school with mediocre education standards, Sylvia like me gained from the fact that the university was trying to spread its net further and diversify its student base at the time when we applied to Girton. Like me she also gained from having a Welsh father who valued learning and believed his daughter merited a Cambridge education. And like me she had Jean Grove as a Director of Studies.

Sylvia has written that “Every time I opened my mouth I let myself down. It was so hard to feel like a success story at Cambridge, or I suspected any place else, if you spoke English the way I did.” I wish I had known she felt like that at the time for, when we were contemporaries, Sylvia seemed to me the epitome of intelligence, self-confidence and ambition.

Of Jean Grove, Sylvia has said, “Her support was transformative.” It surely was, for the grant-assisted field trip and research assistantship that Jean arranged for Sylvia and the article which they co-authored as a result was a stepping stone to gain a Kennedy Scholarship and a coveted place at Harvard.

Cambridge was not easy for many of us Girton girls in those days. Yet looking back now, I conclude that I may have undervalued my university education. I did find it easy to identify with a saying of Ananda Coomaraswamy, quoted frequently in her time by my favorite poet and another Girton College graduate, Kathleen Raine, that it takes four years to get a first-rate university education, and forty years to get over it.

Kathleen Raine live for 95 years so had time to recover. And thankfully, I do feel ‘over it’ now, sufficiently to be able to appreciate the remarkable privilege of having known a great mathematical mind like Mary Cartwright and the brilliance and percipience of climatologist, Jean Grove.

As I look back today, however, it is my memory of the warmth and humanity of these women that stays strongly with me, together with gratitude that they were so open and available to their students; so evidently eager that we should stand on their shoulders and forge the next link in the chain of evolution of women’s education.

Girton has long since become co-educational. I have no doubt that it is a very different experience today than in the sixties when Sylvia Hewlett and I wrestled with our feelings of inadequacy. I so hope today’s women are finding it an altogether less daunting experience than us. And I hope it will not need to take any of them forty years to get over being a ‘Girton Girl’.